In Europe, as globally, platform work remains a growing phenomenon. This article explores how recent developments in Europe affect platform workers’ rights and access to social security. In particular, it considers recent steps toward the appropriate classification of certain workers, changes in working conditions, and the extension of new rights and responsibilities.

In the European Union (EU) alone, as of 2022, there were over 500 active platforms that activate an estimated 28 million workers in a variety of tasks (European Council, 2023). The large and rising number of workers earning income through platforms – whether as a main source or supplemental – has heightened calls for clear regulations to protect the labour and social security rights of workers using platforms.

The prevailing approach to ensuring labour and social security rights for platform workers in Europe has been to first address worker classification. As of June 2021, before recent changes in national regulations, around 90 per cent of platforms classified their workers as self-employed (European Commission, 2021), with implications for access to full labour and social security protections. These limitations, along with the control platforms have over their workers, have motivated court rulings, law reforms and initiatives aimed at re-classifying platform workers as employees with a view to extending to them their full rights. Addressing the issue of classification alone is unlikely to fully resolve the myriad ways in which the platform economy challenges traditional employment relationships and practices. As a result, governments are also strengthening regulations to ensure decent work and social security for all workers, irrespective of their status.

This article focuses on recent or ongoing reforms aimed specifically at covering platform workers, which, in Europe, are primarily situated within labour law, albeit with significant implications for social security (Table 1). A forthcoming article will explore recent developments in social security for self-employed workers that are relevant to platform work given that most platform workers are still classified as self-employed.

| Classification | Labour protections | Social security | Tax related data sharing | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | ||||

| Belgium | * | |||

| Bulgaria | ||||

| Croatia | ||||

| Cyprus | ||||

| Czech Republic | ||||

| Denmark | ||||

| Estonia | ||||

| Finland | ||||

| France | * | |||

| Germany | ||||

| Greece | ||||

| Guernsey | ||||

| Hungary | ||||

| Ireland | ||||

| Italy | ||||

| Latvia | ||||

| Lithuania | ||||

| Luxembourg | ||||

| Malta | ||||

| Netherlands | ||||

| Poland | ||||

| Portugal | ||||

| Romania | ||||

| Slovakia | ||||

| Slovenia | ||||

| Spain | ||||

| Sweden | ||||

| United Kingdom | ||||

|

Green cells represent EU-level legislation (light green = in progress; dark green = implemented). Cells in blue represent national legislation. An * is in place for cases where EU policy superseded national rules. Note: Labour protections and social security provisions in the United Kingdom (UK) stem from rights attributed to the “worker” status, currently applicable to those in the ridesharing sector. |

||||

One approach to ensuring adequate protection of platform workers is via classification of employment status. With the platform economy advancing at a faster rate than the regulations that oversee it, emerging forms of employment relationships have frequently fallen outside of the traditional definitions governing employment. Regional and national courts have increasingly been tasked with deciding cases from individuals and collectives who are questioning the typical default classification of platform workers as self-employed (see Annex A). The cases highlight factors such as algorithmic management, independence to set their own prices, and the consequences this has on de facto subordination. Case law decisions are in turn being taken up by labour inspectorates, tax and social security institutions, competition authorities and prosecutors (Hießl, 2021).

With the gig economy itself evolving rapidly – for example via the use of aggregators and the emergence of local platforms – the claims around employment status are still largely addressed on a case-by-case basis. Specific cases evaluate workers’ employment conditions against the existing guidelines or labour laws determining status. This approach reflects the heterogeneity of platforms and has led to some claimants being granted labour and social security rights. While helpful in its consideration of each circumstance and the multiple factors that determine employment, the case-by-case approach can lead to uncertainty when cases arrive to regional courts and opposite conclusions are reached both within and across countries. In response, numerous proposals, both at national and regional levels, have sought to establish a rebuttable presumption of employment for platform workers, effectively shifting the burden of proof to dispute the existence of a subordinate employer-employee relationship onto platforms.

Presumption of employment

Spain, with the adoption of the Riders’ Law in 2021, initiated what has become a broad trend toward presumption of employment in the region and globally. In the wake of a Supreme Court decision that extended employee status to Glovo workers (see Annex A), the Riders’ Law extended employee status to all other remaining food delivery riders. In effect, it shifted the burden of proof from the individual worker onto platform companies, which would have to prove that the worker is self-employed and not an employee. With this change, riders in the country are now automatically afforded the same level of protections as employees (unless otherwise demonstrated), and platform companies are required to make all applicable social security contributions. Early indications suggest that the law has encountered implementation challenges that, reflecting the fact that this a relatively uncharted territory of labour law (EU-OSHA, 2022).

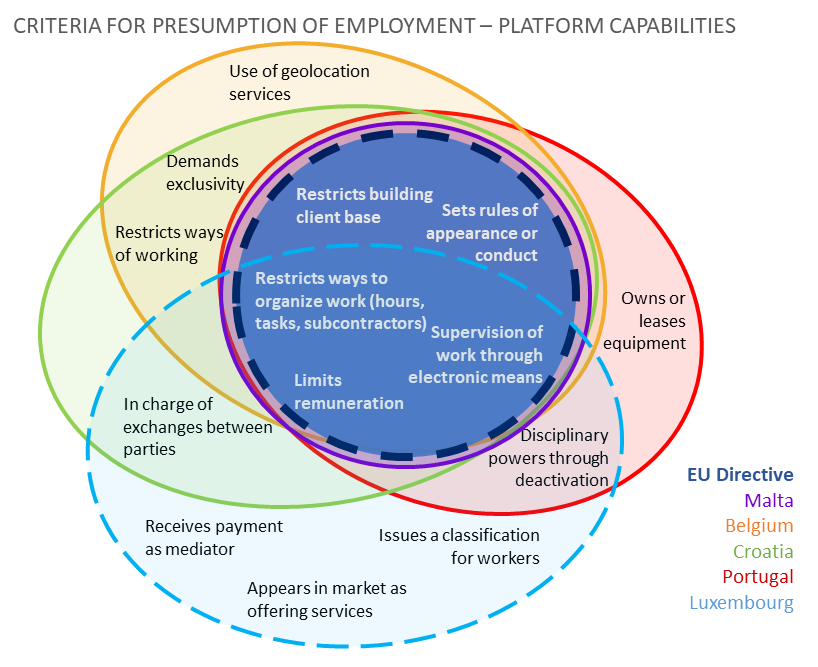

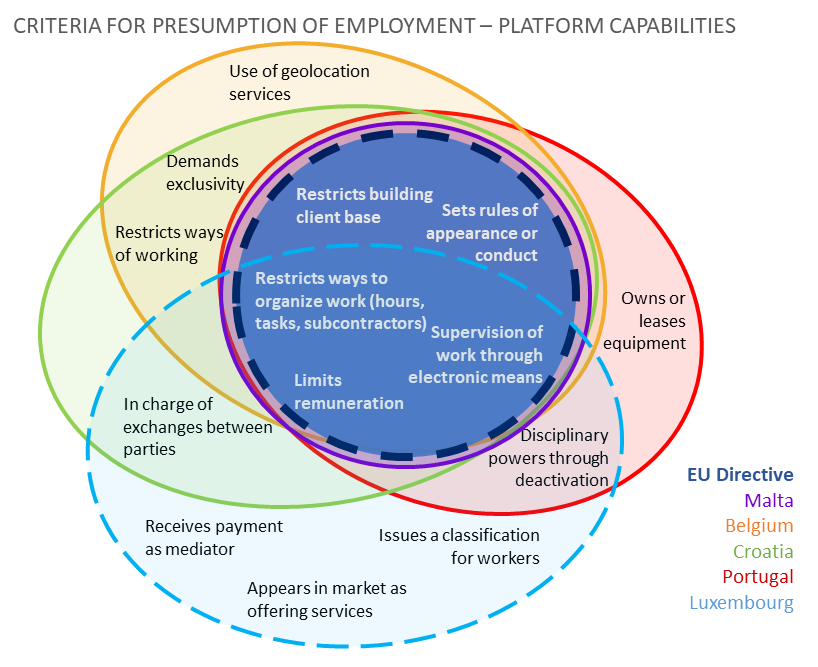

At a multinational level and inspired by the Spanish reform, the European Parliament and Council are actively negotiating a Directive that seeks to regulate working conditions of platform workers. The Directive, presented by the Commission in December 2021, would extend beyond courier workers to include all platform workers. It proposes that workers would be given employee status if two out of five criteria are met (Figure 1). However, the most recent document (Council’s agreed position in June 2023) breaks down the condition of work organization into three and sets the employment status threshold to three out of seven criteria.

Even while still under negotiation, the EU Directive has already started a wave of regulations within EU member states that follow a similar pattern, where changes to employment law are also oriented toward establishing the presumption of employment. For example, as illustrated in Figure 1, national approaches range from adopting the original Directive criteria as they are (Malta), adding additional conditions (Croatia, Belgium, Portugal), or partially adopting the criteria (proposal in Luxembourg). A distinguishing characteristic among the different approaches, however, is the minimum criteria for determining (dependent) employment. The Belgian approach weights criteria differently – three of the total eight national criteria, or two of the original EU ones, while in Croatia and Portugal, no minimum is stipulated. (In Portugal, how these criteria will interact with the newly defined “dependent self-employed” category – which ascribes new obligations for contractors who constitute at least 50 per cent of the income of a self-employed worker – will be an important space to watch.)

The scope of reform varies too, given that in Croatia and Portugal, regulations apply to both digital platforms themselves and to the aggregators to which they can outsource services. The proposal for a Labour code amendment in Luxembourg stands out for stating that the presumption of employment cannot be rebutted if more than two criteria are met. Notably, all these countries are part of the group of countries demanding stronger safeguards following the Council’s position. Moreover, the variety in criteria considered provides an overview of how the Directive might be transposed into national legislation.

Figure 1. Criteria for presumption of employment in established reforms and proposals in Europe.

Figure 1 shows the five criteria conceptually covered by the EU Directive proposed by the EC in 2021. A dashed line represents proposals not yet implemented (EU Directive and Luxembourg legislation). The revised version proposed by the EU Council as well as the countries’ legislations are described in Annex B.

In Greece, reforms affecting platform workers are made through Labour law 4008/2021. This case remains as an outlier on the issue of employment status; rather than a presumption of dependent employment, the presumption in Greece’s law is one of self-employment if the worker is able to (i) use subcontractors or substitutes, (ii) unilaterally choose the amount of projects to undertake at any given time, (iii) provide independent services to any third party, including competitors, (iv) determine the time of providing services. The legislation does not specify who bears the burden of proof, but it must be contrasted with the Directive as the latter gives platforms the ability to rebut the legal presumption based on the “employment relationship as defined by the law, collective agreements or practice in force in the member state in question” (Proposal for EU Directive, 2021).

The adoption of the Directive can also have ripple effects beyond the 27 EU member states. For example, in Serbia, a report by the Commission for Protection of Competition (2022) on the state of competition in the digital platform market recommends that institutions take necessary steps to harmonize national legislation with the current legal acts of the European Union, a key step for the country’s accession. As a result, the Ministry of Trade must begin drafting relevant regulations, and the Ministry of Labour, Employment, Veteran and Social Affairs must review the application of regulations in the field of labour law, applying these to employees of digital platforms and of logistic partners (third party aggregators). Similar processes would need to occur in the remaining candidate countries.

Clarification of guidelines and third categories

In some countries, efforts have focused not on developing new legislation for platform workers, but on addressing potential misclassification by clarifying existing guidelines that distinguish employment status, while noting their applicability to the gig economy. Examples of this approach include the updated “Code of Practice Determining Employment Status” in Ireland, the amendments to the Employment Contracts Act in Finland, and the proposed reform to the Labour Market in the Netherlands. All these initiatives seek to tackle “bogus self-employment” and require a much more detailed evaluation of the working conditions of platform workers.

Finally, it is notable that the discourse around classification still frequently refers to a binary division between employee and self-employed. Some, however, have questioned whether these concepts can adequately reflect the nature of employment in the gig economy or whether a potential third category is needed. For example, the recent rulings in the UK classify certain groups of individuals in the platform economy as “workers”, a category with an intermediate level of rights and benefits, situated between employees and independent contractors. Similarly, food delivery riders in Italy are classified as engaging in “lavoro eterorganizzato” (literally, “hetero-organized work”, denoting its alternative character to traditional forms of employment). Countries such as Austria and Norway also have a legal third category, although it has not been widely used to represent platform workers (PwC Legal, 2022). In all cases, countries must ensure that third category status under labour law translates into adequate financing and access to social security for workers classified as such.

Overall extension of benefits

With the debate on reclassification ongoing, and unlikely to be fully resolved in the short to medium term due to the remaining steps in the EU Directive legislative procedure and subsequent period of transposition into member states' legislation, it is relevant to highlight the steps taken that extend rights and benefits to platform workers no matter their employment status. Efforts include both labour protections and social security coverage (ISSA, 2023) brought about through overarching legislative channels, targeted sectoral regulations, or collective agreements.

Labour protections

By and large, efforts to extend labour protections to platform workers in Europe have focused on improving working conditions, including pay, working time, and occupational safety and health. Legislation in Croatia (Act on Elimination of Unregistered Work) and Italy (Law Decree No. 101/2019) has addressed the issue of adequate pay covering most workers, while collective agreements in Denmark and France are limited to the specific bargaining sector in question – an hourly wage for delivery workers in both countries, and a minimum fare per trip for rideshare workers in France. The collective agreement in Denmark also looks at working time regulations, as does the Occasional Transport Act regulating rideshare activities in Austria. Considering the accentuated exposure to work-related risks among many platform workers, provision of safety equipment and adequate training is also addressed in Denmark, Greece and Italy through collective agreements, legislation, and dialogues, respectively. Finally, in some cases, as in Denmark, Germany, Italy, Lithuania, the Netherlands, and Sweden, agreements only cover workers using a single platform, as opposed to sector-wide measures.

The access to these rights has been facilitated through the extension of collective bargaining rights to workers in the platform economy, in some cases having a ripple effect where rights were also extended to the self-employed. The nature of platform work and its scattered workforce creates particular challenges for workers to organize themselves, especially those in web-based work. To address this, several institutions dedicated to facilitating dialogue and mediating interactions have emerged across the region (Box 1). Previously reserved for employees, the right to organize, participate in strikes, and draft collective agreements is now available to platform workers in Greece, France and Portugal, allowing them to advocate for better conditions and highlight the challenges particular to the gig economy. In addition to regulations that extend channels for conflict resolution, such as the 2018 Transport Law in Portugal, the establishment of these mediating bodies enables a unified approach and consistent results across a highly dispersed working population.

Third party mediation channels have facilitated the accrual of rights. Established by public institutions or privately through platforms and unions own efforts, new institutions dedicated to facilitating dialogue, such as the ones described below, provide a channel where all involved parties can voice their concerns, ideally reaching a common understanding.

|

Beyond working conditions and the various methods to address these across the region, there is also growing attention to transparency, as evidenced by the EU Directive 2019/1152 on transparent and predictable working conditions and emerging regulations governing algorithmic transparency. The practice of using algorithms for human resource management leaves workers unaware of decision-making processes, where elements such as ratings and login periods have a significant impact on earnings and access to remunerated tasks (ILO, 2021). Ensuring workers and regulators have access to information about the rules and criteria used by algorithmic tools to assign tasks or evaluate work is among the priority issues addressed in the EU Directive. It has been adopted under the reforms in Croatia, Italy, Malta and Portugal, and is under dialogue in Germany. In general, better transparency and data availability can enable workers’ associations, including those representing platform workers, to bargain for improved rights more effectively, for example in Lithuania, where access to data on the number of workers and average salaries provided evidence used to back up bargaining positions (European Commission, 2021).

Social security coverage

While the implementation of the EU Directive and classification-related efforts will have big implications for the social security of platform workers, the targeted extension of social security benefits for platform workers has been more scattered, with most efforts oriented toward making platforms act as employers for certain schemes or branches. In France, this was done through Law 2016-1088 of 8 August 2016, which stipulated that platform workers earning more than 13 per cent of their annual social security ceiling, must have access to work injury benefits, either by having the platform cover the contributions for an individual voluntary scheme or by joining a collective insurance scheme that offers comparable benefits. Similarly, the Labour Deal in Belgium that addresses employment classification, also requires platforms to provide accident insurance for all workers. Finally, from February 2020, Italy extended work injury insurance to self-employed workers in courier activities, with platforms required to comply with the obligations of an employer. Single platform collective agreements have also extended wage, pensions, sickness leave and family benefits in Denmark (for example JustEat) and training, pensions, and disability and liability insurance in the Netherlands (Temper, time restricted agreement) (European Commission, 2021).

In addition to the reforms in place, discussions surrounding the extension of benefits are also occurring in Germany and the UK. In the former, the Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs has called for the inclusion of self-employed platform workers in statutory pension insurance, and for platforms to be responsible for contribution payment, and accident insurance modifications (Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales – BMAS, 2020). In the latter, the “Good Work Plan” states that the frameworks for employee and third-category “worker” rights and tax status should be more closely aligned, and that gig and vulnerable workers should be given greater statutory protection.

Importantly, efforts to extend or improve social security benefits to platform workers must be understood within the regional and national contexts in which they are undertaken. While clarification of employment status can affect financing (contribution rates) or access to certain branches, the breadth and depth of gaps in social security coverage for platform workers may vary significantly across countries. As such, employment classification reforms may be less of a determinant of social security coverage under certain national social policy frameworks, especially those with strong universal provisions within a “multi-tiered” framework. Therefore, it is also important to highlight systems such as those found in the Nordic countries, Ireland, Lithuania and Portugal that effectively decouple (basic) access to social security from employment status, or where through subsidies and government contributions, coverage for both employees and the self-employed are already strong.

Other regulations

Alongside reforms affecting worker classification and benefits, further regulations affect digital platforms and their workers. For example, by entering an existing market, but one that operates under a different business model, the ride hail sector has met with large opposition and hurdles, resulting in strong calls for transport laws that regulate this activity. Additionally, tax regulations and data sharing guidelines are placing the revenue generated by digital work platforms under scrutiny and have potential outcomes for collaboration between platforms and government institutions.

Licensing and accreditation for passenger transport sector

Motivated by arguments of fair competition and passenger safety, the ride hailing sector of the platform economy remains most affected by regulations. Overall, these have dealt with specific licensing and accreditation requirements that later allow a worker to legally perform their activity under the same level of scrutiny as drivers in the regular sector (Hungary, Ireland, Lithuania) (European Commission, 2021). A registry of workers facilitates the formalization of their activities, while the regulations also make passenger transfer companies liable for monitoring compliance, as the accreditations are among the documents needed for registration. One example of this can be found in Slovenia, where the reform included a document to promote cooperation between the company and state agencies (ibid). Similarly, in Luxembourg, the path for rideshare is open to workers if they comply with licensing and social security regulations (ibid). Additionally, these reforms have included policies relevant to worker protections. For example, the reforms around licensing and accreditation included working time regulations in Austria, and in Portugal, platforms are required to use “operators” as intermediaries between the platform and the drivers, while the reform also sets out channels for conflict resolution(ibid).

Reporting requirements to tax authorities

A final regulation with significant impact is the EU level seventh Directive on Administrative Cooperation in the field of taxation (DAC-7). Passed in 2021, the Directive includes a set of transparency regulations that extend Common Reporting Standard style rules to digital platforms, requiring these to report information on their sellers to tax authorities.

Applicable from January 2023, DAC-7 requires platforms to collect sellers’ details, including tax identification, bank accounts, and aggregated sales data (e.g. income, amount of services performed, fees and commissions charged by platforms). Such information is recorded per calendar year, with the first report due in January 2024. This data sharing requirement sets an important precedent for collaboration between government institutions and digital platforms. With the DAC-7 already transposed into the national legislation in all but two member states (EUR-Lex, 2023), it has the added benefit of enabling exchange of information among the relevant authorities in each country.

While this regulation does not include tax withholding specifications, nor does it mention social security directly, its impact could extend beyond ensuring tax compliance. The extensive definition of reportable sellers in the DAC-7 covers most gig economy activities, and through the identification of providers, it will generate a large amount of data for a sector in which legislation has largely been based on estimates. If data sharing were to be extended to other institutions, the information on volume of transactions and income generated through digital platforms can be used to inform social security regulations, whether for adequate monitoring of contribution collection, or for the adaptation of frameworks that account for the economic reality of those engaged in atypical forms of work.

Similar reporting measures have also been established in the UK, albeit with a different timeline as reporting will not start until 2024 and is expected to be brought forward on a global scale by the OECD in 2025. Previous instances of such regulations in Belgium and France have required platforms to inform service providers of all tax and social security obligations, with the French legislation also requiring platforms to provide a link to the corresponding authorities (Baker and McKenzie, 2021; Tax News Update, 2023). The reporting rules gain particular importance where there is a unified or simplified tax scheme in place, such as in Estonia, France and Serbia, as data collected on platform workers who partake in these micro entrepreneur systems would be ensuring compliance on both tax and social security contributions.

Final remarks

Ensuring protections – including full social security rights and effective access – for platform workers in Europe is clearly high on the agenda but remains an ongoing process. To date, an overarching trend is to provide workers with protections via attempts to reclassify them as employees. This trend is driven in part by the reality that many platform workers do find themselves in a dependent situation vis-à-vis platforms. However, the emphasis on re-classification also reflects the fact that, historically, employees across most of Europe have leveraged strong bargaining rights to secure robust labour protections and comprehensive social security benefits, while self-employed workers are significantly less likely to enjoy full protections. With many platform workers currently treated as self-employed and engaged in a wide range of activities, reclassification tends to occur on a case-by-case basis. While there is a wave of legislation addressing platform work, national responses are diverse and are developing unevenly (European Council, 2023), as the transport-oriented regulations discussed here show. Furthermore, the implementation of reforms often face backlash or unintended consequences, as has occurred in Spain. Within the region, the EU Directive on platform work is an ongoing process that requires close monitoring due both to its large scope of application and the potential spill over effects as non-member states develop similar regulations.

Given the predominant classification of platform workers as self-employed, improving the social security situation of platform workers is inextricably linked to wider efforts to improve coverage for the self-employed. In countries with comprehensive system that offers comparable level of benefits, or where access to benefits is not tied to employment status, the impact of reclassification on coverage decreases, and social security reforms can sharpen their focus on portability or cross border protection. Finally, many of the issues faced by platform workers also affect workers in other vulnerable forms of employment. Ultimately, in Europe as elsewhere, the task of fully incorporating platform workers highlights the importance of adapting existing models to a wider and more flexible framework that responds to the changing world of work, with systems able to identify, quantify and combine workers’ different income sources (Schoukens and Weber, 2020).

References

Baker; McKenzie. 2021. Belgium: DAC 7 light reporting obligation(s) introduced for digital platforms in the sharing and gig economy. Brussels.

BMAS. 2020. Neue Arbeit fair gestalten. Eckpunkte des BMAS zu „Fairer Arbeit in der Plattformökonomie“ (Pressemitteilung). Berlin, Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales.

Commission for the Protection of Competition. 2022. ИЗВЕШТАЈ О РАДУ КОМИСИЈЕ ЗА ЗАШТИТУ КОНКУРЕНЦИЈЕ ЗА 2021 ГОДИНУ [Work report for the year 2021]. Belgrade.

EU-OSHA. 2022. Spain: the ‘riders’ law’, new regulation on digital platform work (Policy case study). [S.l.], European Agency for Safety and Health at Work.

EUR-lex. 2023. National transposition measures communicated by the Member States concerning: Council Directive (EU) 2021/514 of 22 March 2021 amending Directive 2011/16/EU on administrative cooperation in the field of taxation. Luxembourg, Publications Office of the European Union.

Eurofound. 2021. Sharing Economy Council (Initiative) (Record number 2874, Platform Economy Database). Dublin.

European Commission. 2021. Study to support the impact assessment of an EU initiative to improve the working conditions in platform work. Luxembourg, Publications Office of the European Union.

Hießl, C.. 2021. “The Classification of Platform Workers in Case Law: A Cross-European Comparative Analysis”, in Comparative Labor Law & Policy Journal, Vol. 42, No. 2.

ILO. 2021. World employment and social outlook 2021: The role of digital labour platforms in transforming the world of work. Geneva, International Labour Office.

ISSA. 2023. Platform workers and social protection: International developments. Geneva, International Social Security Association

Ombuds Office. n.d. FAQs. Frankfurt on the Main, Testbirds GmbH.

PwC Legal. 2022. Gig Economy 2022. Antwerp and Brussels.

Ministère du Travail, du Plein Emploi et de l’Insertion. 2023. ARPE (Autorité des Relations sociales des Plateformes d’Emploi). Paris.

Schoukens, P.; Weber, E. 2020. Unemployment insurance for the self-employed: A way forward post-corona (IAB Discussion paper, No. 32/2020). Nuremberg, Institute for Employment Research.

Tax News Update. 2023. "France implements regulations under DAC7 with respect to digital platforms". 27 February.

Legal documents

Real Decreto-ley 9/2021, de 11 de mayo, por el que se modifica el texto refundido de la Ley del Estatuto de los Trabajadores, aprobado por el Real Decreto Legislativo 2/2015, de 23 de octubre, para garantizar los derechos laborales de las personas dedicadas al reparto en el ámbito de plataformas digitales. Boletin Oficial del Estado. Madrid

Digital Platform Delivery Wages Council Wage Regulation Order, 2022. Malta.

Lei n.º 13/2023, de 3 de abril Altera o Código do Trabalho e legislação conexa, no âmbito da agenda do trabalho digno. Assembleia da República. Portugal

Law on Amendments to the Labour Law, December 16, 2022. Croatian Parliament. Croatia.

Loi portant des dispositions diverses relatives au travail (1). 3 octobre 2022. Service Public Federal Emploi, Travail et Concertation Sociale. Belgium

Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on improving working conditions in platform work on improving working conditions in platform work. December 2021. European Commission.

Proposal for a Directive of the European Parliament and of the Council on improving working conditions in platform work on improving working conditions in platform work - General approach. June 2023. European Council.

Proposition de loi N° 8001 relative au travail fourni par l'intermédiaire d'une plateforme. Chambre des Deputes. Luxembourg

| Country | Year | Parties | Status Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | 2021 | Federal Administrative Court | Employee (two cases) |

| 2021 | Federal Administrative Court | Self-employed (two cases) | |

| Belgium | 2019 | Enterprise Court of Brussels v UberX | Self-employed |

| France | 2018 | Court of Cassation; Take Eat Easy | Employee |

| 2020 | Paris Labour Court; Deliveroo | Employee | |

| 2020 | Court of Cassation; Uber | Employee | |

| 2021 | Lyon Appeals Court; Uber | Self-employed | |

| 2022 | URSSAF v Deliveroo | Employee (social sec) | |

| Germany | 2019 | Higher Labour Court of Munich | Self-employed |

| 2020 | Federal Labour Court v Roamler | Employee (single case) | |

| Italy | 2019 | Court in Turin | Collaborator (third cat) |

| 2018-2020 | Labour Tribunal of Turin v Foodora; Supreme Court | Employee | |

| 2020 | Tribunal in Palermo v Glovo | Employee | |

| 2021 | Florence Civil Court | Self-employed | |

| Netherlands | 2018 | Amsterdam Civil Court v Deliveroo | Self-employed |

| 2019 | Labour Courts v Deliveroo | Employee (multiple cases) | |

| 2019 | Amsterdam Civil Court v Helping | Self-employed | |

| 2021 | Amsterdam Appeals Court v Deliveroo | Employee | |

| 2021 | Amsterdam Districts Court v Uber | Employee | |

| Spain | 2018 | Court in Valencia v Deliveroo | Employee (single case) |

| 2020 | Supreme Court v Glovo | Employee | |

| Switzerland | 2020 | Vaud appeals Court v Uber | Employee (single case) |

| 2022 | Federal Court v Uber | Employee | |

| United Kingdom | 2021 | Supreme Court v Uber | Worker (third cat) |

| Country | Criteria as they appear in national legal documents |

|---|---|

| EU Directive (v2) |

Article 4 For the purpose of the previous subparagraph, exerting control and direction shall be understood as fulfilling, either by virtue of its applicable terms and conditions or in practice, at least three of the criteria below: (a) The digital labour platform determines upper limits for the level of remuneration; (b) The digital labour platform requires the person performing platform work to respect specific rules with regard to appearance, conduct towards the recipient of the service or performance of the work; (c) The digital labour platform supervises the performance of work including by electronic means; (d) The digital labour platform restricts the freedom, including through sanctions, to organise one’s work by limiting the discretion to choose one’s working hours or periods of absence; (da) The digital labour platform restricts the freedom, including through sanctions, to organise one’s work by limiting the discretion to accept or to refuse tasks; (db) The digital labour platform restricts the freedom, including through sanctions, to organise one’s work by limiting the discretion to use subcontractors or substitutes; (e) The digital labour platform restricts the possibility to build a client base or to perform work for any third party. |

| Belgium |

Article 15 (…) § 2. For ordering digital <platforms>, employment relationships are presumed, until proven otherwise, to be executed within the framework of an employment contract, when the analysis of the employment relationship, it appears that at least three of the following eight criteria or two of the following last five criteria are met:

§ 3. The presumption referred to in § 2 may be rebutted by any legal means, in particular on the basis of the general criteria set out in this law. |

| Croatia |

The assumption of the existence of an employment relationship in work using a digital work platform Article 221 m

|

| Luxembourg |

Chapter 2. Presumption of employment contract between platforms and service/work provider Art. L. 371-3 When one or more of the following criteria are met:

However, when at least three of the criteria mentioned above are met, then the existence of the employment contract is established, without contrary proof being admissible. |

| Malta |

Article 4. Legal presumption of an employment relationship (…) the burden of proof shall be on the digital labour platform or the work agency, as the case may be, when declaring that there is no such employment relationship by proving that it does not control directly or indirectly the performance of the digital platform work because it does not fulfil at least four (4) of the following criteria in relation to the person performing the platform work:

Provided that, any proceedings relating to such claim shall not have a suspensive effect on the application of the legal presumption |

| Portugal |

Article 12-A 1 - Without prejudice to the provisions of the previous article, the existence of an employment contract is presumed when, in the relationship between the activity provider and the digital platform, some of the following characteristics occur:

|